1981

|

By GERRY BARKER

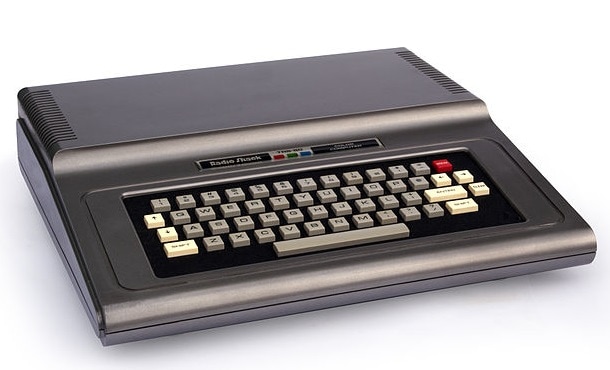

(Originally published July, 2009) Whether you spell it with the ending “t” or without, videotext was the first rung on the ladder that would eventually lead us to the World Wide Web. And in 1981, there was great excitement worldwide over its prospects. European countries were blazing the trail for the rest of us. In England it was Prestel. In France, it was Minitel. Each had impetus as part of government-funded initiatives. Here in the United States, the landscape was different. Our government wasn’t ready to fund an information device in every home. But private corporations were serving the ever-growing number of personal computers with ASCII-text applications. CompuServe was the leader. The Source was another. It wasn’t pretty but it was pretty amazing. Maybe a good place to insert a note about "ASCII" -- American Standard Code for Information Exchange, one of the many new words this journalist aded to his vocabulary. Basically a common way to display text characters every computer understands. Those ones and zeros, you know. The idea of moving information around via telephone lines, modems and computers was gaining acceptance. And this notion of having a private electronic mailbox where you could exchange messages instantly with friends, co-workers or even strangers – that was something this side of mind-boggling. In the midst of all this activity, as industry giants jockeyed for position, little attention was given to a newly-launched online service that emerged from a place in Texas that proudly wore the label, Cowtown. That place was Fort Worth. Also known as Where the West Begins -- the home of world class museums like the Kimbell and the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, or for the fighter jets produced by Lockheed, not to mention the Stockyards and the world’s biggest honky tonk, Billy Bob’s. Fort Worth was also home for the newspaper of record, The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and electronic retailing giant, The Tandy Corp., parent company of Radio Shack. And in 1981, the business interests of those two very different companies would come together to create what would eventually become one of the very few online success stories of the decade. But that’s getting ahead of the story. In 1981, I had been working in the Star-Telegram newsroom for just over 10 years. Starting as a copy editor on the afternoon paper (when just about every town in America had an afternoon and morning paper), I had enjoyed an interesting mix of jobs. They included local copy desk chief, rock music writer, op-ed columnist and features production editor. For someone who aspired to work on a newspaper since the sixth grade, it was my dream career -- editing, writing, working elbow to elbow with the men wearing green eye shades. But my career was about to take a hard right turn, thanks to Tom Steinert-Threlkeld. Tom, a graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism and the Harvard Business School, wore several hats at the Star-Telegram. One was reporter for the business section, specializing in electronics coverage. Another was Research Director – Electronic Publishing for the Star-Telegram’s parent company, Capital Cities Communications (later to become Capital Cities/ABC when they swallowed up the ABC Television Network). For the latter, he was charged with investigating the full range of emerging technologies and reporting back to corporate. Phillip J. Meek, who served as president and publisher of the Star-Telegram and later, President/ ABC Publishing Group as well as senior vice president for ABC after the Capital Cities/ABC merger, recalled Steinert-Threlkeld’s hiring in a November, 1997 interview: “In 1979, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram hired its first and only graduate straight from the Harvard Business School. (I) was impressed with a former newspaper reporter who had gone on to get business training. As an added plus, he indicated a strong desire to spend the first year or so as a business writer in the newsroom, which was a most contrarian attitude for an HBS grad of that era. “As a prolific writer, Tom made an immediate impact on the business pages of the Star-Telegram, concentrating on technology and the Tandy corporation, which was emerging as an early leader in personal computer development and sales. He traveled constantly to industry meetings and built up a wide range of contacts. After about 18 months, he indicated a desire to move onto the business side at what turned out to be a propitious time. “The head of publishing for the parent company, Capital Cities Communications, had concluded that its chairman and chief executive officer, Tom Murphy, needed someone to bring him up to speed on the fast -changing technology side. Steinert-Threlkeld was assigned that task on a part-time basis, still operating out of Fort Worth.” In my 1997 interview with him, Steinert-Threkeld recalled the circumstances that led to his involvement: “In November or December of 1979,” Tom said, “then-managing editor Henry Holcomb asked me, as electronics writer, to write up a report on the potential impact of electronic publishing on newspapers. This was for some look-ahead-at-the-next-decade project he had been charged with completing, presumably by or for Phil Meek. My report was to be just one piece of this overall package of looks-forward regarding different facets of editorial operations. “Well, the report came out at about the time that CompuServe was initiating an attempt to produce content for its inchoate online service by recruiting newspapers to be content providers. The Star-Telegram was among those broached. Holcomb and Meek, as I recall it, asked me to take a look at what CompuServe had going.” Tom “was very unimpressed. At 300 baud, it was very slow. And its menu structure was very cumbersome and uninspired. So I recommended that we not participate and that we do something on our own. Joe Donth (Star-Telegram director of data processing, soon to play a key role himself) became involved at this point, and, in his office one day, we hit on the idea of using predefined keywords to simulate keyword searching, because it would not require much processing power. To this day, I think we were the first to hit on this idea for an online service, now widely used by AOL and others. “In any case, as Joe and I tried to figure out a way to justify doing our own online service in-house, there was a contact from (Tandy CEO) John Roach, through Meek, to inquire about our interest in doing a videotext service. Videotext was kind of hot back then, with a lot of attention on Knight-Ridder's Viewtron project (Capital Cities and Knight-Ridder entered into a data share agreement in November, 1981) and Times-Mirror Gateway project. Tandy Corp. hoped to move a lot of videotext terminals, really the forerunner of what we now are calling network computers. The videotext servers would provide all the info and services; users would just have these cheap dumb terminals that plugged into their TV sets, for displays. “Roach also wanted to sell the servers, with videotext services and modems driving sales of Tandy computers. I can't recall the original Tandy machines that were supposed to serve as the servers. But they were early in the TRS-80/Tandy line.” As we would all later discover, “they proved well under-powered for the purpose. “As for why I championed the idea of doing something, it was clear to me that this was not just some extension of newspapering, but an entirely new medium. There seemed nothing so challenging or with as much long-term promise as figuring out how to make the most effective use of the new method for effectively using text and graphics to communicate: The cathode ray tube.” It was this notion, that we were about to embark on something that was “not just some extension of newspapering, but an entirely new medium” that sparked my interest. That plus the fact I had just completed a major assignment, titled “The Information Age,” co-authored by Tom and John Paul Newport, a former quarterback for Yale who had recently joined the staff. Meek recalled that “Tandy pushed the newspaper to join together and start a local videotext service, which Tandy saw as a way to sell home computers, and Tom was assigned responsibility for that effort, working with the MIS director, Joe Donth.” On paper, the joint venture appeared to be good fit. As the local newspaper, we brought content and credibility. As a leader in consumer technology, Tandy brought its computer and retailing expertise. It was also a time when sales of personal computers were on the increase and Radio Shack was among the early leaders with its line of Tandy TRS-80 Models I, II and III, as well as the Color Computer. But this local information service would be primarily directed toward a new Tandy product, the “videotex terminal” Steinert-Threlkeld mentioned. Low slung, in a molded dark gray case with a built-in keyboard, the Tandy TRS-80 Videotex Terminal was a “dumb terminal” built solely to access databases. Retailing for $399, it had a built-in 300-baud modem (state-of-the-art at the time, moving text across the screen at a blazing 30 characters a second) and RF modulator, which connected the unit to a television set for its display. There was a small red light on the top that glowed when the unit was online. The first models came with 4K of RAM, expandable to 16K. While hard to imagine by today’s standards, it had a curious way of downloading information. But more on that shortly. By November, 1981, a plan had been developed for the deployment of this new joint Star-Telegram/Tandy venture, which now had a name:“STAR-Text” (later modified to StarText). Why StarText? Early on, Steinert-Threlkeld told us we needed a name for this new service – and finding a name that wasn’t taken might be tough. One day, at the copy machine, it came to me. “The Star-Telegram is a partner and the service will deliver information as text,” I told Tom. “How about StarText?” He liked it. We applied for the trademark and copyright and our new venture had a name. Among the primary objectives put forward in the plan were: -- Test consumer acceptance of text and graphical information. -- Conduct market research of its services and features. -- Promote the sales of personal computers. -- Become a profitable enterprise. -- Brand the Star-Telegram and Tandy as information and technology leaders. The plan also addressed some key guidelines. Interestingly enough, I think most would agree the guidelines set forth then are every bit as critical now to the success of today’s Internet ventures: -- It must be low cost (today that translates to "free") -- It must be easy to use. -- It must be easy to understand. -- It must be highly immediate (provide the latest news). -- It must be tailored to serve specialized information needs. The service, “to carry the name STARText, will be a 24-hour information service offered to residents of Tarrant County on a subscription basis. It will offer general news, weather and other information to consumers as well as specialized information products to specialized audiences.” The Star-Telegram wasn’t the only information provider. Another was Merrill Lynch, who would be offering subscribers stock prices, commodity prices and national news related to stock and commodity services. There also would be information from Radio Shack on its products as well as Fort Worth area computer clubs. Another interesting twist: Radio Shack would obtain airline schedules for DFW International Airport. As Steinert-Threkeld noted, it was decided, against the conventional wisdom of the day, that subscribers would access information on StarText by using keywords rather than menus. At that time most of the online consumer services of the day required users to “branch” through databases via menu selections. Typically, you were presented a set of options. Depending on your choice, you were given a second set of options, and so forth – a process that was often tedious, time-consuming and laborious (but great for the services that charged by the minute). This specification that the system be engineered for keyword access to categories of information was indeed a new concept. While new ground was being broken in navigation, the actual retrieval of the information was much more cumbersome. Due to the restrictions in the software, access would be on an “advanced entry”- method, sometimes referred to as “dump and disconnect.” The subscriber would enter their ID, plus up to four requests for information, or keywords, offline. The terminal or computer makes the connection. The requested information is downloaded into the user’s local memory and the connection broken. Subscribers then read the information offline and would have to repeat the whole process if they have additional information requests. Despite the magic and hype of actually reading a newspaper remotely on a screen, with information moving along at a snail-like 300 baud, the experience was fairly painful, even for the die-hard tekkies and early-adopters. So a provision was made that Tandy would upgrade the software to provide true “online” access within six months of launch. This was viewed as critical if the service were to expand and grow. Other interesting points spelled out by the plan: -- At launch, subscribers initially would pay $5 a month for StarText service. After the online upgrade became available, the price would go to $7.50. The Star-Telegram would handle the billing, which would be in three-month increments. -- Promotion and marketing: The Star-Telegram would provide house ads on a fixed schedule; Tandy would do direct mail and in-store demonstrations at all area Radio Shacks. -- It was suggested that terminals be provided free to several city and state officials to allow politicians to be in touch with local events. -- The Star-Telegram pledged to hire “sufficient personnel to operate the database on a continuously updated basis from 6 a.m. to midnight seven days a week.” -- The host computer would be a Tandy TRS-80 Model II. The system would store 3,000 frames of information, stored on four floppy drives. -- Future expansion would include interactive features, shopping services and archived news retrieval. As time would prove, all ideas which were right on the money, literally. -- Service would launch in the early part of 1982. With a few exceptions, Charles Phillips, senior vice president for Radio Shack, accepted the plan and the wheels were set in motion for residents of Tarrant County to be among the first in the country to have its local newspaper available to them on a personal computer. Cowtown was about to take its first steps into the Information Age. Staffing With Donth overseeing the technical details, Steinert-Threlkeld tackled the news staffing issue. His approach was asking for three volunteers from the Star-Telegram newsroom – editors with a sense of adventure, not afraid to take a few risks, willing to take “the New Media plunge.” Having just completed the “Information Age” project (a three person, multi-part series on new information technologies), I was already primed. But the attraction went beyond that. As a journalist, I was fascinated with the notion of providing readers news as it happens – like television – but with a depth that television couldn’t provide. The combination of immediacy and the unlimited news hole, not to mention the possibility of having a two-way dialogue with our readers, was a powerful inducement. This had the potential to revolutionize journalism and what a great opportunity to be in on the ground floor. It also was the chance to help in some small way to architect a new medium. And how many times does an opportunity like that come along in a career? Of course, these were all arguments I used when it came time to convince my wife Pam. Her reaction wasn’t nearly as enthusiastic as mine. What pained the most is that I would be giving up writing, which she knew was my first love. All I could say was, “Trust me – one day this online stuff was going to be big.” Of course I had nothing to back up that claim except a gut feeling. As for writing, it would just be on hold for a little while. So after some more discussion, some soul searching and a few prayers, I told Tom to count me in. I would be joining two other newsroom veterans, John Durham, who would head up the team, and Jim Smead. John came onboard first to begin the initial planning; Jim and I would join soon afterwards. Meek remembered those events from a slightly different perspective: “Partly as a result of the split responsibilities with his corporate role, there was some confusion about oversight of the StarText project,” said Meek, “and Tom tended to act independently of the local management structure. One result was an unauthorized raid of the newsroom, and three editors were hired away at higher salaries to work on StarText.” Call it unathourized or entreprenurial, I’m fairly certain StarText wouldn’t have enjoyed the success it did if it had been run as a traditional department of the newspaper. So it was probably fitting we started in such a nontraditional way. The other member of the team was Joe Donth, the no-nonsense, hard-nosed director of the Star-Telegram’s MIS department. Known for his business acumen, Donth had a penchant for problem solving and a reputation as an exceptional programmer. He also had another quality that cast him into a leadership position throughout the history of StarText: Joe was a visionary. While his primary job would always be running the ever-expanding and demanding MIS operation, Joe’s true love was inventing the future. Without Joe’s involvement and guidance, StarText would have never survived to reach adulthood. Thus began what Joe would later characterize as “the most unauthorized project” in the history of Capital Cities. |

BISON: It's Not a BuffaloBy GERRY BARKER

While StarText was barely in the planning stages, 30 miles to the east, the Dallas Morning News was busy deploying its own online service. In 1981, Belo, the parent company of the Dallas Morning News, launched the service it called BISON – the acronym for Belo Information Systems On-Line Network. If it wasn’t the first, it certainly was among the first local online services launched by a U.S. newspaper. BISON had its genesis in 1980, when Gean W. Holden was hired early that year as Director of Corporate Research/Technology and head of Belo Informations Systems, a division of the A.H. Belo Company. Holden wasted little time in putting the wheels in motion to create a consumer videotex service. In a memo prepared for the 1980 annual report, Holden detailed the steps that led to BISON’s creation. In March of 1980, Holden held early discussions with BISON’s partners, Texas Instruments, Sammons Cable and Dow Jones, another pioneer in distributing financial information online. Holden had just returned from the Viewdata Conference in London, where he was energized by what he saw and heard. He called it “the best conference I’ve ever been to because there was so much to be learned.” (The year before, the Britain Post Office launched Prestel, an early online service streamed via telephone lines to dedicated terminals. It had been in development since the mid-70s.) The partners reconvened in early April at the TI Corporate Engineering Center to hammer out a proposed budget for the launch of the “Park Cities Experiment.” Park Cities, an affluent Dallas suburb, was chosen as the test market for a new Sammons “data retrieval network” that would include access to stories from the Morning News. A story published in the Morning News on May 16, 1980, under the headline, “Sammons unveils special cable network,” provided details on what Park Cities residents could expect. Quoting from the article: “Sammons Communications Inc. said Thursday it will offer 200 of its Park Cities Cable Television subscribers access to an elaborate data retrieval network, beginning this summer. “Dow Jones & Co. Inc. of Princeton, N.J., publisher of the Wall Street Journal, and Belo Information Systems, a division of the A.H. Belo Corp. of Dallas, which publishes The Dallas Morning News, also will participate. They will supply subscribers with business and financial information, news and other data via the home computer access system. “Merrill Lynch & Co. of New York will join the experiment to provide brokerage information. “Jim Whitson, president of Sammons Communications, announced the agreement in Dallas, along with Gean Holden, director of Research and Technology for Belo Corp., and William L. Dunn, vice president and general manager of Dow Jones. “The Sammons Park Cities project will be the first anywhere to involve large numbers of cable television subscribers access to information banks in several cities from private home terminals. “ ‘Our idea is to offer a nearly limitless data retrieval capability with our cable TV system,’ Whitson said. ‘By adding home terminals, a keyboard and a screen, the cable system becomes an electronic newspaper and financial encyclopedia. This is the kind of 2-way cable systems most companies have only thought of in terms of the future.’ “In structuring the Park Cities data retrieval system, Sammons will follow the format of a recently successful Dow Jones project involving individual access by four families and two businesses in the Las Colinas development in Irving (Texas). “Participants will be linked by cable and satellite through their computer terminals with a central Dow Jones computer at South Brunswick, N.J. and the Belo Information Systems computer in Dallas.” It continued: “For Belo Information Systems, the project will be the first experiment with individual, consumer access of data bases. Holden said information available to the system from The Dallas Morning News will include the current day’s news, stories, sports, weather and restaurant and entertainment guides. “Belo Information Systems also is expected to begin experimenting with classified advertising, which will be accessible to the home terminal. A typical local problem that could be solved with a classified access system would be house hunting. “With a computer terminal, the user would feed the system a variety of information, detailing the basic requirements, _location, number of bedrooms and price range, Within seconds a list of homes for sale, fitting the described requirements, would appear on that screen.” Decades later, that’s exactly how many of us do it. By May, the pieces were falling into place. The staff for BISON began to take shape as personnel were interviewed and hired. Offices were established at The Registry, an upscale Dallas office complex on LBJ Freeway. Arrangements were made for the installation of the TI equipment. BISON would be hosted on Tandem Nonstop computers, considered the Cadillac of its time. At the same time, meetings were held with local automobile dealers to gauge interest in taking their business online. Holden comments, “After two attempts that didn’t work out very well, we took the terminal out to several dealers for on-site demonstrations and that proved to be very positive.” There were also discussions with the phone company about placing the white pages online. The conclusion: “It would not be cheap and would not be easy, but it could be done.” All the staff (by one estimate 35 in all) were in place by the end of July and getting familiar with the TI hardware and software. In August, communications links between downtown and The Registry offices were in place and work was proceeding on organizing the database for the Park Cities experiment Later that month, BISON got its first unveiling at demonstrations for executives at Sammons and the Belo Board. September was devoted to debugging and tweaking the software. Two DEC terminals were installed in the Morning News newsroom to accommodate data transmissions to The Registry. The scene was set for the impending launch of the Park Cities experiment the following month. The Park Cities Experiment went live Oct. 19, 1980. But, in a story all too familiar to new media pioneers, its debut wasn’t entirely smooth sailing. “Just before we began the service,” writes Holden, “we installed the new disks, everything crashed and we lost the database.” They were able to install the TI terminals in the homes and “we were able to get the service going despite all the problems.” That same month, BISON was showcased at online shows in San Francisco (Information Industries Association) and San Diego (LINK Conference), where people were “amazed that we were able to get the system on the air in such a short period of time.” The Park Cities Experiment concluded on Dec. 19, 1980. Writing in the first annual report after the company became publicly traded in December, 1981, Joe Dealey, chairman of the board and chief executive officer, noted: “Through Belo Information Systems Division, the Company is engaged in interactive electronic distribution of information to the home. In 1981 the Company spent almost $1 million in this new venture, an increase of approximately $670,000 over the prior year.” In June, 1982, one month after the launch of StarText in Fort Worth, Belo suspended BISON. The 1982 annual report had this to say: “In June, 1982, we suspended the test phase of Belo Informations Systems On-Line Network (BISON), our home information subscription service. This program was introduced in August of 1981 as a research and development effort to determine the technical dimensions, market potential and user acceptance of interactive home videotex. Although the BISON system was a technical success, we concluded that the commercial market for interactive home videotex systems is not sufficiently developed to justify the continuation of significant expenditures. However, we believed we learned a great deal from the BISON project which will serve us well in the future. We will maintain a minimal staff to keep abreast of technical and market developments in this field and provide us flexibility to re-enter this market once the videotex market materializes." Years later, one former Belo manager characterized BISON this way: "We would have done as well digging a hole, dumping in $3 million and setting it on fire." Regardless of the outcome, you have to give them credit for jumping in the pool first. The Cue Cat? That's another story. |